We live in the age of brand experience. Yet, again and again I find that brands the world over fail to create a strongly differentiated and positive brand experience. Three back-to-back brand experience failures makes me write this today.

The first experience was on December 3rd morning. We were in Bangkok, where I had been on work, and staying at the Pathumwan Princess Hotel. My wife had visited me for a few days during my stay and she was checking out. I went to the front desk with her explaining that she was leaving but I was staying and would check out the following day as per the original reservation. Once my wife left I went back to the room to discover that my Internet connection had been terminated and I could not log on with my name and room number as I had done the past several days. It took several phone calls and a full half hour before my internet connectivity was restored. An otherwise pleasant stay was blemished.

THE next day, at Suvarnabhumi Airport, I spied a Jo Malone shop. As my wife likes their perfumes and her birthday was around the corner I went there. As is customary at Jo Malone, tester bottles for all the perfumes we re arranged in a semi-circle on a table at the front of the store along with the paper strips to test out the perfumes. I picked out a bottle and tried to spray some on the scent strip but nothing came. Looking at the bottle I realized it was empty. Never mind, I tried a second perfume, same story. When I looked at the display more carefully, the majority of the bottles were empty! I asked the store clerk what was going on and she said they had no stock! I was not only disappointed but annoyed. Why oh why would Jo Malone spend money on a store at the Bangkok airport only to annoy customers with a wide ranging stock out? Wouldn’t it be better to just shut the store when there was no stock rather than annoy customers? Or, if stocking was challenging, perhaps shut down the store permanently, rather than annoy potential customers who may have shopped for it elsewhere and now may not buy Jo Malone again.

Most recently, yesterday, December 5th, I tried to set up a data connection with Bharti Airtel. I bought the device and the SIM card along with 1GB of data at the Airtel store at Gariahat in Kolkata. First, it took forever, including the sales clerk 1) repeatedly trying to upsell me from a prepaid to a postpaid connection and then making a mistake in his instructions on how to sign on the application form, leading to it having to be filled out a second time.

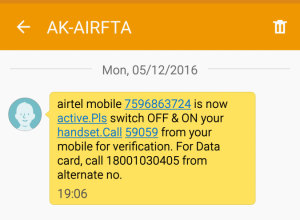

Once that was over, he informed me that in about an hour I would receive an sms message and I would have to go through a set of steps to activate my account. The sms did come and I went through the steps required to activate the account. I received an sms message indicating I had been successful and that my account had been activated. Pleased, I went off to sleep as I had an early morning Skype call.

In the morning, I connected to the Airtel WiFi and my computer showed that I had “internet access”. However, tries as I might, restarting the Airtel WiFi modem, restarting my computer, reconnecting to the modem,… I couldn’t get online on Skype or using my browser. All the time the internet connection showed that I had “internet access”. When I went to the Airtel store again this morning after they opened at 11 am, I was told that they had to activate the connection from the store and that was done only when they reopened at 11 in the morning. Thus, in fact, at 7 in the morning I did not have connectivity even though it showed I did and I had been informed by an sms generated by Airtel the night before that I had connectivity. Again, a feeling of deep frustration and lack of trust or loyalty towards Airtel.

So what’s in common for all these failures? It seems that organizations don’t understand that brand experience is not about what the marketing people do, but about what the organization behind the brand does as a whole to deliver on the promise made to the customer. For Pathumwan Princess the nice physical facilities, great location, nice restaurants, fantastic gym and pool were undone by either incompetence on the part of the front desk staff or the IT system which logged both guests out when one checked out but the other remained. At Jo Malone, their interesting and distinctive fragrance product line was undone by a wide spread stock out. In the case of Airtel, it was a failure of the automated customer response system that generated messages that set false expectations. In each instance the failure was on some part of the organization other than marketing.

Why does this occur? The problem is that in most organizations, brands are managed by the marketing department and the marketing department does not have control over the various other organizational functions that are crucial in delivering brand experience. It is time that organizations understood that managing a brand is an integrated organization wide activity and, thus, each brand needs to be managed as a business, cutting across functional silos, so that the brand head can orchestrate a complete brand experience. This requires moving responsibility for the brand from within marketing to the level of the business head. Some organizations already do this. Thus, for example, at Diageo, brands like Johnnie Walker are businesses unto themselves with all the business functions reporting in to the global brand director, who in turn reports to the Diageo CEO. More companies need to take this to heart and manage their brands from the C-suite.