The last fortnight saw the second quarter announcements of performance from both the Coca Cola Company and PepsiCo.

Although PepsiCo significantly outperformed Coca Cola’s negative 1% growth in net sales (and a 3% decline in profits) by reporting a top line growth of 4% (and a higher profit rate), they both seriously underperformed when compared to AJE, the Peruvian purveyor of Big Cola. AJE with global sales of $2bn is a minnow compared to Coca Cola or Pepsico, but according to the Financial Times, “AJE’s global sales grew at an average of 22 per cent a year from 2000 to 2013”!

The AJE Group and its brand Big Cola, interestingly owes its foundation to the reign of terror by the guerrilla movement Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) in the 1980s, which led the Añaños family to flee their farm. Forced to think of how to survive, and seeing the withdrawal of the soft drink giants from the market, the five siblings (four brothers and one sister) started making an orange flavored beverage they called Kola Real in 1988 in their courtyard, bottling it in recycled beer bottles, and selling it door-to-door to neighborhood residents and mom and pop outlets in the city of Ayacucho!

The product caught on, and in 1991, the Añaños siblings founded the AJE Group to bottle and expand the business, expanding to smaller cities like Huancayo, Bagua, and Sullana first, then pretty much throughout Peru in a step-by-step fashion, before finally arriving in the Peruvian capital, Lima, in 1999.

In 2000 it began international expansion, targeting neighboring Venezuela and Ecuador. In 2002 it entered Mexico, followed by the countries of Central America in 2004. Around the same time, it also started to add to its brand portfolio. In 2001 it added bottled water under the brand name Cielo, in 2005 Pulp, a citrus fruit drink, and in 2006, Sporade, a hydrating drink. That same year, it also set up its corporate headquarters in Madrid, Spain. In 2010 it entered India, Vietnam, and Indonesia. Today, it is present throughout Latin America and the United States. In Asia it has expanded in to Thailand as well. And aside from Kola Real, Cielo, Pulp, and Sporade, it also owns Cifrut, Volt, and the Big Cola brands.

From the very beginning, AJE focused on serving less affluent consumers, offering lower prices; as an example, to enter Lima in 1999, the Kola Real campaign positioned the brand as “The Fair Price Drink”. And Kola Real prices are approximately 25% lower than that of its main MNC competitors’ offerings. To keep prices low, AJE needs to keep costs low. It does so by paying close attention to its entire value chain, stripping costs aggressively wherever possible. For instance, AJE manufactures its own beverages, unlike its MNC competitors like Coca Cola and PepsiCo, which rely on an extensive network of independent bottlers, because this allows them to produce their beverages at a lower cost.

AJE was also a first mover in to PET bottles, which are ubiquitous today. Not only were these bottles cheaper but they were lighter and less fragile, making them much less expensive to buy, use, and distribute. To keep costs low, AJE invests in partnering with micro-entrepreneurs who use their own transport to distribute AJE’s brands. 92% of AJE’s sales are through such direct partnerships, with only the remaining 8% going through wholesalers, who are more expensive. This distribution model not only helps AJE keep costs low, but also 1. enables them to penetrate deep in to its markets, going to remote locations which remain un- or underserved by their MNC competitors, and 2. penetrate new markets rapidly.

AJE’s success is not just due to lower costs, it also adapts to local markets. For instance, in Asia, it sells a Big Cola without caffeine, to adapt to local market needs. Or when, in Indonesia, the currency weakened, it launched a 300 ml pack priced at Rp 2000 to remain attractive to its target consumers. Today, four short years after entering Indonesia, AJE holds almost 40% of the Indonesian carbonated soft drink market of 1 billion liters per annum!

AJE’s success has drawn the attention of the big MNC operators, who have tried competing by aggressively offering promotional prices and increased spending on advertising. However, this only works in the short term; poorer consumers revert back to AJE’s brands once the promotional prices are withdrawn.

What is interesting is that the dominant MNCs in this space, Coca Cola and PepsiCo, seem unable to deliver growth in the way AJE does or come up with a clear response to AJE’s success. What can we learn from AJE’s success story? There are lessons for both wanna be AJEs, or the so-called EMNCs, as well as for MNCs. These lessons have been detailed in our book The New Emerging Market Multinationals: Four Strategies for Disrupting Markets and Building Brands, and here we review the key points that jump out from AJE’s story:

Lessons for EMNCs

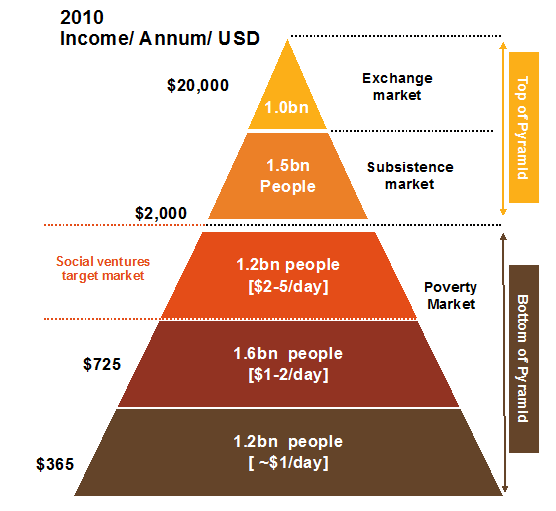

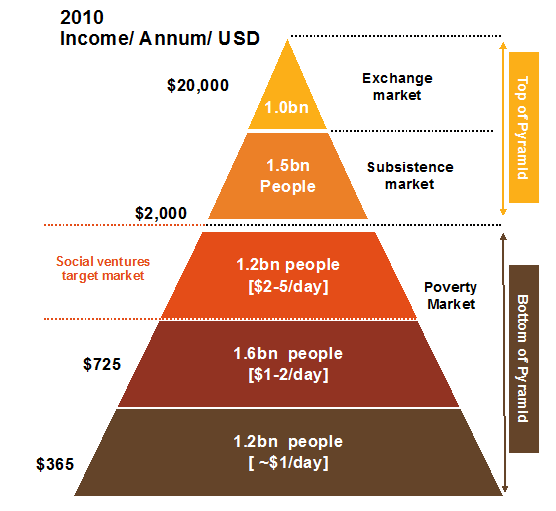

- Identify a target customer group that is underserved—in the case of AJE, these are consumers at the bottom of the pyramid, who number 4 billion, and those who live in less accessible locations.

- To avoid head-on competition, penetrate deep in to emerging markets; traditional MNCs target the affluent in the metropolises and bigger cities.

- Focus relentlessly on costs, stripping costs from all elements of the value chain.

- Lower costs through owning your own manufacturing.

- Leverage the lower costs to not only price lower, but also to innovate and localize your offering to meet local needs.

- Expand slowly but systematically, initially expanding the product range to increase the share of wallet of existing customers.

- Expand in the next stage by targeting the same target segment as targeted at home, across geographies.

Lessons for MNCS

- MNCs have vastly larger budgets and thus far it seems that, that is what they are leveraging to try and compete through promotional pricing and brand building. Perhaps they are better off in shifting these vast budgets away from promotion pricing, which does not work with bottom of the pyramid consumers, to brand building.

- The freed up dollars can be used to develop low cost brands, perhaps leveraging the master brand, and creating a brand architecture that can successfully reach down to the bottom of the pyramid.

- Exploit the superior market knowledge that has been accrued over the years of presence in many emerging markets to develop localized offerings, again where possible leveraging the brand architecture.

- Transfer knowledge more effectively across geographies. After all, EMNCs like AJE do not have the organization structures or processes to be able to do this as effectively.

- Learn from the EMNCs and cut costs relentlessly across the value chain. MNCs simply do not do this well.

Surprisingly, PepsiCo and Coca Cola do not seem to be sensitive to these learnings! The future of growth is in the emerging markets and among the bottom of the pyramid consumers there. Failure to learn these lessons and deploy strategies based on them to compete effectively in these markets and among bottom of the pyramid consumers is likely to be perilous for the future!