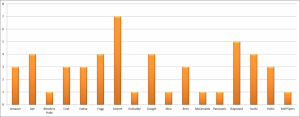

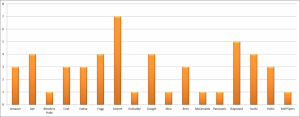

Watching the test match between India and England on TV in India I was staggered at the level of advertising repetition that I experienced. During one hour, I decided to keep track of the commercials aired. The brands and the number of times they advertised during the hour period are below. As one can see, 17 different brands advertised during the hour. These brands covered a broad range of categories across products (e.g., Blenders Pride, Ceat, and Panasonic) and services (e.g., Amazon and McDonald’s), as well as domestic (e.g., Idea, Fogg, and Kent) and global (Axe, Google, and Suzuki) brands. Of the 17 brands that advertised, 11, or a whopping 65%, aired their ads three times or more, with Gionee, the Chinese mobile phone maker showing the exact same creative a mind numbing 7 times during the hour!

This brings me to the main point of this blog. Why so much repetition? Theory has it that consumer response to repetition follows an inverted-U shape. That is, initially, consumer response increases with repetition, as consumers learn about the brand, but then declines, as repeatedly watching a brand’s advertising becomes boring and irritating. The point at which additional exposures has a negative impact depends on the complexity of the advertising, the amount of attention consumers pay to advertising, and the like. Most lab studies, which show participants ads embedded in a TV program during a viewing episode of less than one hour find that optimal impact is reached with three exposures, declining thereafter. According to Siddarth and Chattopadhyay (1998)[1], field studies find that incremental repetitions starts to have a negative impact on consumer responses somewhere between 12 to 15 exposures over a two-month period. Indeed, Siddarth and Chattopadhyay (1998), show that, across product categories, consumers are likely to channel switch while watching TV, if they see a given commercial more than 14.5 times, and also show that channel switching negatively impacts purchase behavior. Importantly, these results were obtained using a dataset spanning two years!

To those of you who don’t know about cricket, a day of test cricket spans three, two-hour sessions. The ads above were repeated throughout the day. Thus, 65% of the brands above would have been seen 18 times or more while viewing a single day’s play; for Gionee, the most advertised brand, there would have been 42 exposures. Across the five days of a cricket test match, and ardent follower of the game would have seen 65% of the ads a nauseating 90 times or more and even the lightly advertised brands, well above the 15 exposure threshold. Gionee’s advertisement would have been seen 210 times! However, one slices the data, there is cause for concern. Are these brands overexposing themselves to their detriment?

The research data on repetition effects I refer to above are from American consumers. So one question to ask is, are Indian consumers different? My intuition suggests that they cannot be that different. Seeing an Amazon ad 90 times, an Axe ad 120 times, a Raymond ad 150 times, and a Gionee ad 210 times cannot reasonably be expected to not turn off a consumer through over exposure. Repetition beyond a reasonable level is annoying and turns consumers off a brand, be they American or Indian. Thus, I would submit that there is a significant degree of over-advertising in the Indian marketplace, which is not doing the sponsoring brands any good, and most likely hurting them. I’d like readers to weigh in with data from Indian consumers in support or otherwise.

[1] Siddarth, S. and Amitava Chattopadhyay (1998), “To Zap or Not to Zap: A Study of the Determinants of Channel Switching During Commercials,” Marketing Science, 17 (2), 124-138.